"Everyone I Don't Like is Psymposia"

The Emotional Child's Guide to FDA Approval of MDMA-AT, now in The New York Times; plus, Psychedelics Today promotes "safe words" for restraint, and a new report shows how therapists are indoctrinated

Since late summer, my Psymposia colleagues and I were aware that Andrew Jacobs and Rachel Nuwer were brewing a hit piece against us for The New York Times. When they finally asked me for an interview in early November, I had two requirements: a list of the questions in advance, and permission to record the conversation.

By that point, Jacobs and Nuwer were already well known for promoting industry talking points. After the FDA’s advisory committee meeting in June — where the committee overwhelming voted ‘no confidence’ in Lykos’ MDMA-assisted therapy application — Nuwer published a puff piece for the BBC that underemphasized problems with the trials and implied the committee members just didn’t ‘get’ psychedelic therapy. (The Psychedelic Science Funders Collaborative [PSFC] — the network of wealthy philanthropists that was responsible for funding the completion of MAPS’s Phase 3 clinical trials on MDMA-assisted therapy — circulated Nuwer’s article in the first stage of its PR campaign to pressure the FDA to override the committee’s non-binding vote.)

Meanwhile, Jacobs’ output at The New York Times has exclusively parroted PSFC’s preferred narratives about the psychedelic industry. On December 17, 2024, for example, he published an article that described psychedelics as “rewiring…the brain,” asserting that “[psychedelic] treatments require hard work and a willingness to confront potentially uncomfortable emotions and trauma.”

(For years, my work has discussed how these narratives are oversimplistic and irresponsible. By framing what’s often considered a last-ditch treatment option as requiring the bravery to submit to suffering, the field has created conditions where vulnerable and desperate people are pushing themselves to endure acute distress — which at times has included outright abuse from psychedelic therapists. When patients go on to struggle after their sessions, the field has primed them to internalize their failure: they must not have “done the work.”)

On February 4 — when the NYT hit piece was finally published — I laughed out loud when I saw the absurd headline: “How a Leftist Activist Group Helped Torpedo a Psychedelic Therapy.” It read like it was intended as satire: a victimized pharmaceutical company with millions of dollars on the line, tyrannized by a highly coordinated, shadowy cell of anticapitalist terrorists motivated by nothing more than a desire for retribution. (My mom texted me her reaction: “This article makes you out to be a remarkably powerful person.”)

But it wasn’t satire; it was red meat for the MAGA crowd, published on the same day that a Senate panel voted to advance pro-psychedelic pseudoscience peddler Robert F. Kennedy Jr.'s nomination for health and human services secretary to the full chamber.

They targeted me exactly how my sources were afraid they would be targeted if they came forward. I chose to speak up at the FDA’s advisory committee meeting because others weren’t able to do so.

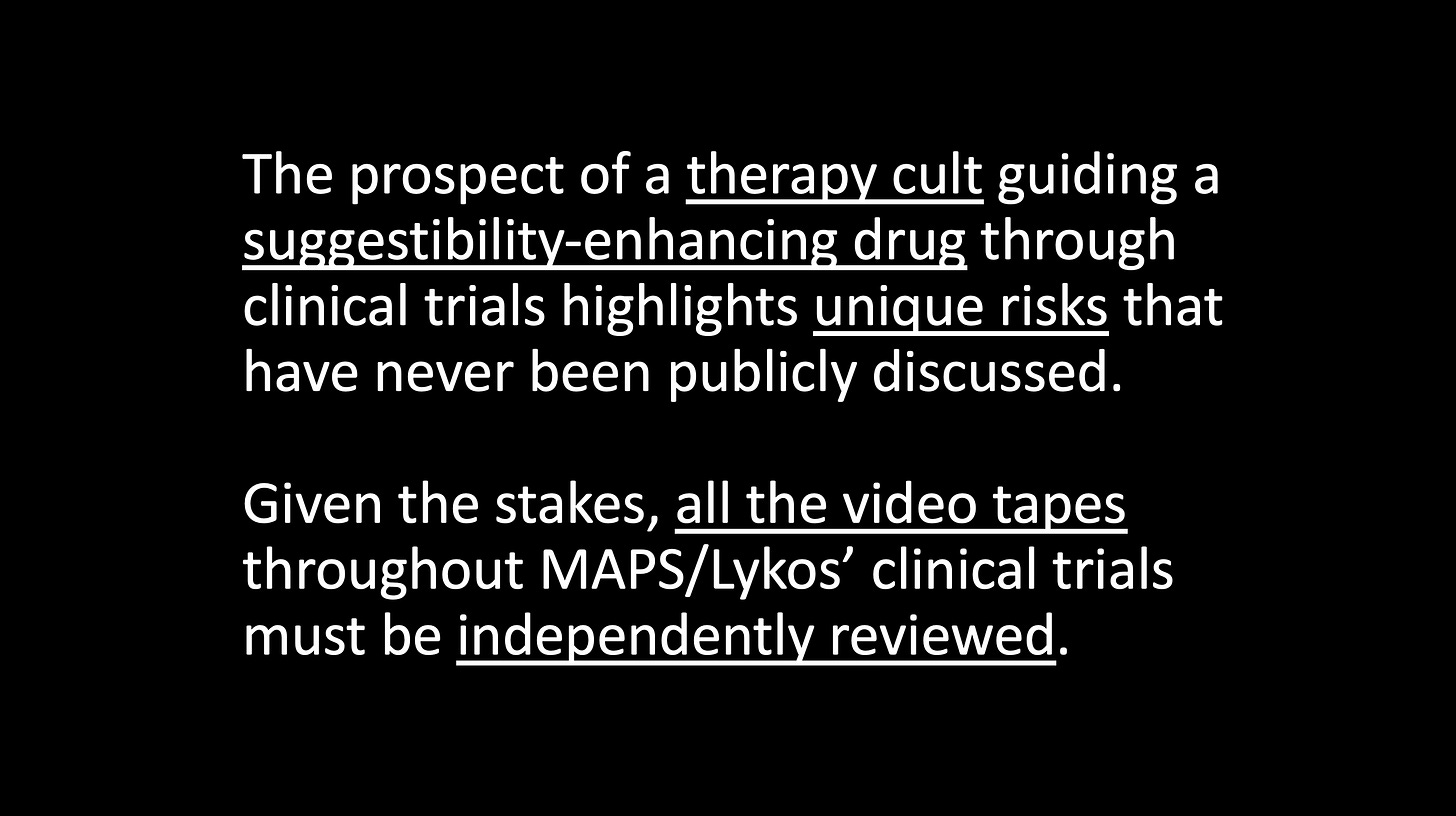

And the FDA listened. Most of my evidence remains non-public, but I shared my sources and evidence directly with FDA investigators, which was the appropriate venue for this information. Subsequently, the FDA requested a full independent review of Lykos’ Phase 3 clinical trial videos. Although it’s impossible to know how the FDA arrived at this decision, I had recommended a review of the trial videos on a slide that I presented to the FDA’s advisory committee on June 4:

Jacobs had assured me in writing that we would have ample opportunity to respond to any allegations before the story was published: “We will provide you with plenty of time to respond to any allegations that are made in the story so you can be confident about that.” We only saw the allegations once the story was published, however.

They didn’t get basic facts right, like the total number of Psymposia members. Three of us presented at the advisory committee meeting, as I told the journalists during our interview, and we followed the FDA’s own guidelines for disclosure.

Since February 4, Jacobs has gone on to make even more extreme claims. Speaking on a radio show about the story, he falsely asserted that Psymposia “[Psymposia] had seven or eight separate experts who were all singing the same tune. And I think that helped create this atmosphere of doubt that the ad com [advisory committee] members seems to have felt there was a lot of red flags here and they couldn’t approve.”

The reality of the matter — which is damning for MAPS/Lykos — is that the critical presentations during the meeting’s open comment period were not coordinated. The fact that these critical presentations were so complementary reveals how credible these concerns actually were. But that’s not convenient for people like PSFC’s Genevieve Jurvetson, who has admitted that her “moonshot goal” for 2025 is “to get MDMA across the finish line.”

Meanwhile, in a sudden and unprecedented development that felt almost symbolic, I lost the ability to use my dominant hand due to a severe sprain in the days following publication. Just as an actual billionaire-funded PR campaign was mobilizing lies about me on a national stage, it became much harder for me to communicate my perspective, which was completely absent from the story. (Someone even set up a new Wikipedia page for Psymposia right before the story launched — as one would do if they wanted to ensure that the story’s smear was memorialized.)

On February 6, I posted a preliminary response on my social media channels:

“It's disappointing — but not surprising — that journalists with close ties to MAPS have resorted to such a transparently partisan political attack. This piece is an opportunistic attempt to politicize whistleblowers with a narrative that appeals to the Trump administration. While Jacobs and Nuwer attack Psymposia and me personally, they have failed to refute our core claims, which remain important and unrebutted. To be clear, their attacks are flatly incorrect and underscore their desperation to distract from the real story: that MAPS’s handling of its clinical trials was a disaster, and that Lykos is in financial disarray.

“To obscure this fact, the article offered a caricature of my research and of Psymposia's broader work in the field. I describe my actual motivations in a recent AJOB commentary: Lykos has never acknowledged how the on-camera physical and sexual abuse from its Phase 2 clinical trial was enabled by the therapy's reliance on Grofian “focused bodywork.” The Phase 2 participant had tried to alert the FDA to this connection for years, and it was only after those initial attempts were unsuccessful that we felt obligated to communicate this to the advisory committee, before this dangerous practice could be scaled.

“If MAPS had listened to this participant’s concerns when the abuse took place, they could have made their therapy safer years ago. I am not opposed to the psychedelic industry, but to the normalization of pseudoscientific practices when vulnerable groups are at stake.”

Although the NYT article was clearly designed to “controversialize” and divest me of professional credibility, I’ve still participated in a few meetings related to psychedelic ethics in the weeks since then. Those meetings have prompted me to pose this question: How do researchers in the field understand the definition of pseudoscience, and how many recognize the risks of pseudoscientific/non-falsifiable methodologies in psychedelic therapy? It seems like there are wide differences of opinion on this topic, and the answers have significant implications for research on psychedelic-related harms and communication about those harms. If some researchers in this field embrace pseudoscience to the extent of expressing hostility to researchers who are voicing concerns about pseudoscience, what does collaboration on “psychedelic harm reduction” look like, in practical terms?

In a 2020 paper on “the authoritarian dimension of pseudoscience,” Angelo Fasce et al. describe how social communities devoted to pseudoscience engage behave with hostility towards those who challenge their collective worldview:

“These factors lead individuals to fervently endorse ingroup conventions as social imperatives that must be respected – an inflexible conception of social norms that leads them to reject outgroups’ conventions, including their beliefs and values. […] Group centrism – that is, the degree to which individuals strive to enhance the ‘shared-reality’ of their collectivity – involves uniformity pressures, such as denigrating the dissenters or extolling the conformists, in order to achieve group consensus.”

“Echo-chambers and partisan media...foster social conceptions associated with pseudoscience, such as group bias and, consequently, authoritarian rejection of hostile information. Echo-chambers are often exploited by evidence-resistance groups that effectively promote denialism and pseudo-theories. In general terms, it is important to encourage people to counter the false-consensus effect and harmful intellectual submission by making their voices heard.”

It’s clear from this literature that the NYT narrative is exactly what you would expect from a community of “true believers” in pseudoscience (synonym: a therapy cult) that retaliates against dissenters and demands intellectual submission.

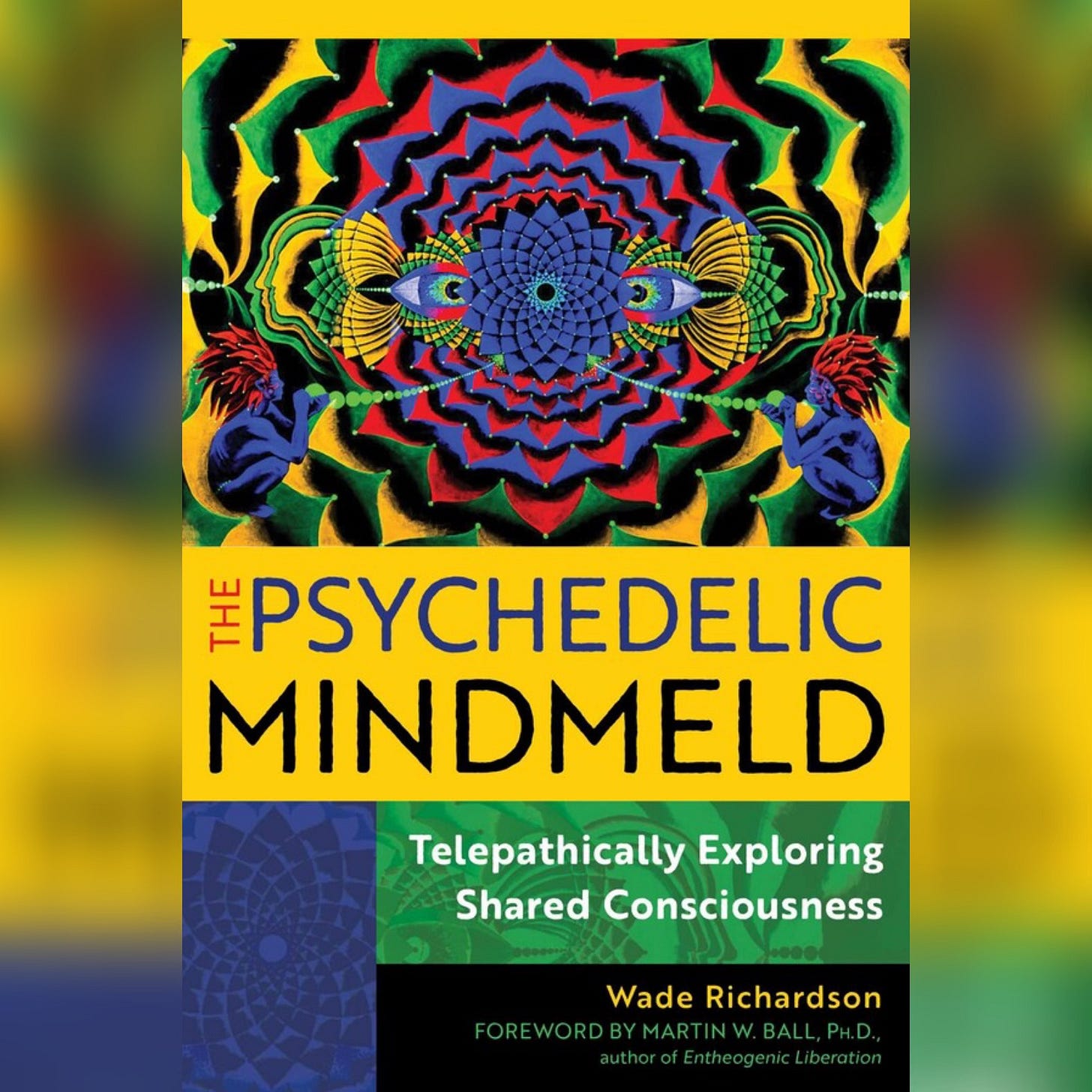

The fact of the matter is that much of the psychedelic field thinks telepathy is a valid tool for psychedelic therapy. Most others think that no one would ever take ‘therapeutic’ telepathy seriously. As a result, both groups think that Psymposia must be acting in bad faith for engaging in sorely needed harm reduction and public education relative to the first group.

It’s telling that the NYT article didn’t engage with any of my core points, which I shared with Nuwer and Jacobs:

I discovered the same use of a “safe word” to moderate touch during psychodramatic enactments of struggle in the MAPS therapy protocol itself.

Gold publicly admits that she opened her ketamine practice to provide MAPS therapy before MDMA approval.

Despite the NYT’s photograph of Gold’s technique, Gold admitted that her patients lie down while they are engaged in psychodynamic enactments of struggle via focused bodywork on high doses of psychoactive substances, as I quoted in previous posts. Applying pressure while a client repeatedly asks for the touch to stop amounts to restraint.

A Phase 3 participant of Veronika Gold had reached out to me prior to my presentations.

“Safe words” for “psychodramatic enactments of struggle” are a central feature of holotropic breathwork

It’s clear that a major reason that so many people in the psychedelic ecosystem are convinced that Psymposia is a “bad faith” and deserving of hostility is that the methodology promoted by Veronika Gold is widely promoted in the psychedelic underground. This is especially the case among groups that incorporate Grofian holotropic breathwork or its various offshoots — including Dreamshadow, where Joe Moore and Kyle Buller of Psychedelics Today were trained in “transcendental breathwork.”

In a 2023 podcast episode titled “The Power of Our Breath: A Deep Dive Into Breathwork,” Moore and Buller discuss a Grofian principle that was foundational to the MAPS therapy model — namely, that trauma is processed (or metabolized) by intensifying distress:

“You know, this idea that you kind of need to make, really intensify the sensation, in — the phrase Stan [Grof] loves is, ‘The full expression of an emotion is its funeral pyre.’ So like, we want to encourage people in this method to make it bigger, and bigger, and bigger, and therefore this thing has less and less energy, and therefore less influence over your subconscious process through having it dissipate, energetically.”

As the many Grofian therapists working in MAPS’s clinical trials were aware, facilitators could amplify participants’ distress by applying “focused bodywork,” as I discussed in my last post. Previous editions of the MAPS therapy manual described focused bodywork euphemistically, as “touch (usually in the form of giving resistance for the subject to push against), which aims to intensify and thereby release tensions or pains in the body that arise during therapy.” The full context of this practice can only be understood by reading Grof’s writings on holotropic breathwork, which Rick Doblin has acknowledged was the basis for the MAPS therapy.

In a 2018 podcast where Moore and Buller discuss the “components and mechanics of breathwork,” they endorse the same reliance on a “safe word” to mediate facilitator touch during reenactments of trauma:

“When we’re engaging in bodywork like that, the only word that we respond to is ‘no’ — or [actually] ‘stop,’ sorry! [...] Some people could sit there and scream at us, and tell us to get off of them. We would typically kind of see that as psychic material arising, especially if somebody might have had, like, an abuse background, and they’re kind of reliving that. Um, so, the magic word is ‘stop.’”

Although Buller struggled to recall the appropriate safe word during a casual podcast conversation about the modality, I have never found a discussion of the risks of relying on a “magic word” when patients are experiencing full-blown flashbacks on high doses of psychoactive drugs known to impair verbal recall, regardless of whether the substance is ketamine or MDMA.

Ultimately, I’ve been painted as a villain because so many people in the psychedelic field are implicated in promoting and using this unsafe practice. Due to the pseudoscientific therapeutic ideology that they’ve been trained into, these practitioners believe that this method works. Since they exist in an echo chamber where this practice is normalized, they’ve assured themselves that they’re good people who couldn’t be implicated in promoting a dangerous modality that would unquestionably cause harm to vulnerable patients at scale. And then, when independent researchers like me step forward to draw attention to a topic that clearly needs to be more openly discussed, these practitioners all agree amongst themselves that we must be the problem.

Psymposia’s concerns are corroborated in new case report

The same month that the “cultophilic” side of the field attempted to intimidate and marginalize Psymposia in The New York Times, a case study published in BMC Psychiatry corroborated many of our concerns about the field’s dominant healing ideologies. The case report — titled “Prolonged adverse effects from repeated psilocybin use in an underground psychedelic therapy training program” — describes the harrowing account of a 71-year-old therapist (“Dr. A”) who was in the process of being indoctrinated into an underground, pseudoscientific worldview. This underground training was presented as necessary to develop competencies for working in psychedelic clinical trials.

Dr. A’s story presents clear evidence that the underground, pseudoscientific foundations of MAPS’s therapy was unsafe to scale. It is a textbook example — the inevitable outcome of the dominant pseudoscientific paradigm of psychedelic therapy, wherein acute distress is framed as emerging symptoms that must be processed through amplification. The facilitators’ mantras are deeply familiar to those of us who have been studying the pseudoscientific underground: “Trust the process.” The way out is through suffering.

In accounts of harm across both the psychedelic underground and clinical trials, all of these elements are reoccurring:

“The leaders described challenging experiences as a necessary part of the healing process.”

The leaders’ teachings framed integration as the participant’s responsibility. (This idea appears in the common saying that ‘you have to the do the work.’) When the participant struggled with prolonged adverse effects (PAEs), she internalized this as “[her] own fault. I was told I did not do the work to integrate and that’s why I had the negative experience.”

When the participant expressed reservations about continuing with additional dosing sessions, the leaders continually “presented reasons for her to continue with the training and that her distressing experiences were ‘part of the process.’” They assured her that the distress was preparing her for the final retreat, which “would turn it all around and give [her] the final answer.”

As the PAEs worsened, “They advised her specifically to not seek psychiatric intervention or medication as it could impair the process of ‘rebirth’ following her ‘ego death’ and would prolong her symptoms.” (As a reminder, Rick Doblin has publicly acknowledged that “the essence of the [MDMA] treatment approach” is a Grofian “death-rebirth” process.

Throughout the case report, there are signals that this therapist-participant had internalized aspects of the leaders’ worldview, which contributed to her sense that she needed to push herself to endure additional dosing sessions. When things went increasingly sideways, that worldview encouraged her to blame herself for her the distress, and to view potential psychiatric remedies with suspicion and anxiety.

As the report notes, her belief in the leaders’ worldview began to waver after the final retreat, when the extent of the SAEs’ impact disrupted the indoctrination process:

“This deference [for the leaders] diminished when she reported to them her loss of appetite with significant unintended weight loss, and was told, ‘that’s part of the medicine perfecting you.’ Later, after one of the leaders told her to ‘stop acting like a victim’ when voicing her concern about the extent of her functional impairment, she cut ties with the Institute, no longer believed her psychiatric and physical symptoms were part of a healing or transformative process, and became fearful that she had done irreversible harm to herself, which lead to passive thoughts of suicide and the psychiatric hospitalization three months after the sixth retreat.”

All of this also occurred during MAPS’s clinic trials, according to the trial participants who communicated with me before I presented to the FDA’s advisory committee last summer:

“On multiple occasions Dr. A’s concerns were deflected, interpreted as a sign of growth, attributed to her own putative shortcomings, or used as a predicate for further dosing sessions or individualized treatment sessions. Experiences of individuals in vulnerable positions, such as Dr. A, have been examined in the context of various forms of institutional abuse. […] Some of the dynamics experienced by Dr. A., such as framing her distress as part of a necessary growth process or isolating her from seeking medical care, may also be understood within the broader context of coercive control. […] Notably, Dr. A was specifically advised by the leaders to not seek psychiatric treatment as her experience was conceived of as a necessary feature of an intended purification process, rather than as an adverse effect. Within such narratives, the interruption of a purification or incomplete purification is sometimes considered a major harm or error.

The revolving doors between the underground and MAPS’s clinical trials

Dr. A’s conclusion is ultimately identical to the position that Psymposia has held for years: “Dr. A., upon reflecting on her experience, felt strongly that the current discourse on psychedelics so far had underemphasized the possibility of significant harms, which contributed to her decision-making and risk appraisal during her involvement with the Institute and its psychedelic training program.”

As the case report’s authors emphasize, the leaders’ worldview were directly implicated in the harms that she experienced:

“This case also presents an opportunity to identify contextual factors of the broader set and setting that contributed to this use pattern and perpetuated it by denying, obscuring, or reframing harms, despite the patient having recurrent and escalating distress. From her initial positive experiences with psilocybin, she concluded that psychedelics not only had therapeutic potential but also might induce a global change in consciousness towards political and societal betterment. Osterhold (2023) observed that such idealizations may frame psychedelic use as part of a high stakes mission that proliferates use and obscures harms. Most notably, Osterhold (2023) also remarked that psychedelic experiences, through their “noetic quality” (i.e., sense of imparted knowledge), can significantly inflate self-confidence and thereby embolden charismatic but reckless, and even malicious, leaders who may underestimate risks and over-estimate their abilities to assist those experiencing adverse events.”

This is exactly what I presented to the FDA in my written comment, which I posted to this substack as “MAPS is an MDMA therapy cult.” The psychedelic field as a whole has a responsibility to study these ideologies as a central component of harm reduction.

From my perspective, it’s essential to look at the ways that these issues are continuous with some aboveground clinical trials. Responding to Josh Hardman’s Twitter/X post about this case report, Robin Carhart-Harris commented that the example illustrates how it is “Lawless in the underground…” — but this completely overlooks the revolving door that existed between the underground and MAPS’s clinical trials.

Across the field, clinical trial therapists are routinely referred to underground training to develop core competencies. Although trial clinicians are encouraged to keep their underground activities discrete, the normalcy of this practice is acknowledged in published articles:

From “Psychedelic-Assisted Therapy Training: An Argument in Support of Firsthand Experience of Nonordinary States of Consciousness in the Development of Competence,” published in the journal Psychedelic Medicine: “Many seeking competency with [psychedelic-assisted therapy] will continue to pursue psychedelic experiences, driven by individual values and needs for professional development. This is analogous to our experience with abortion...before legalization, where a growing number of [individuals] will circumvent [the] law.... [T]herapists seeking personal experience with [psychedelic-assisted therapy] feel obliged to break the law to become more effective therapists. At this time of unprecedented inadequacy of mainstream treatments, we are called to support, not obstruct, therapies with demonstrated positive outcomes.”

In a 2024 essay in Ecstatic Integration, Jules Evans wrote about “The risks of underground psychedelic training programmes,” where academic researchers have experienced serious harms, including sexual assaults. In this account, multiple clinicians working on a psychedelic clinical trial trained with the same underground program: “In 2021, Matthew was hired as a clinician on a psychedelic clinical trial. He wanted to get training to help him run the trial as effectively as possible. […] Matthew considered enrolling in a psychedelic facilitator training programme to prepare for the trial. […] [A] co-therapist involved in the same clinical trial as Matthew came back from a Delta Centre retreat incredibly effusive about the experience and about Richard and Rebecca’s healing powers. She hosted a dinner for some of the psychedelic research team at Matthew’s university.” (I recommend reading this full account, which provides important insight into these dynamics.)

Many of these therapists believe that the pseudoscientific underground principles taught to Dr. A are state of the art, because this is what much of the field teaches. Pseudoscientific practices are often persuasive to in-groups, despite remaining fundamentally flawed and unsafe to normalize as medical treatment.

When experienced therapists like “Dr. A” don’t run into trouble, they often return to work in clinical trials having internalized the underground pseudoscientific framework. As in the example above with Matthew’s co-therapist, they return home effusive about the efficacy of this approach to psychedelic therapy, with a new identity as part of the psychedelic vanguard that is ushering in a new era of planetary consciousness. Like Dr. A, many of them aren’t aware of how this approach can go wrong — because the framework is non-falsifiable. Like facilitated communication, the framework includes explanations that reframe adverse outcomes in a manner that shields the ideology from scrutiny. Among insiders, it’s inconceivable that the ideology is giving rise to harms.

Indoctrination or enculturation into a pseudoscientific community occurs when the in-group promotes a conceptual framework that validates pseudoscientific beliefs.

Evidence of this indoctrination of therapists is apparent in a 2021 Psychedelics Today podcast with Veronika Gold and her co-therapist, Harvey Schwartz. Schwartz is explicit about how psychedelic therapists are encouraged to believe they have extrasensory powers of perception: “I’ve seen this happen on retreats, where therapists who had previously been more non-transpersonal actually open up to this more intuitive gift, or intuitive ability they have. And then they start going through a big identity crisis around like, ‘Well what if I go back and tell my [mainstream therapist] colleagues back home that I’m, you know...hearing ancestral voices, or, you know, picking up things [telepathically]. And so, I think there's a lot of support needed for therapists who are going through the, the transformation to become psychedelic therapists.”

Schwartz’s belief in the need to keep these special powers discrete is commonly held in these communities, as an excerpt from Stan Grof’s book Holotropic Breathwork makes clear: “Self-exploration using holotropic states thus tends to create a distinct subculture that accepts or even takes for granted certain realities that an average person in our culture would find weird or even crazy. This is particularly true if a group has shared holotropic experiences for an extended period of time, for example, in a month-long workshop, in our training for facilitators, or in an ongoing group, which meets at regular intervals over a number of months. [...] We ask them to...carefully choose people with whom they may share the experience.”

Extrasensory perception (ESP) and telepathy are central features of Grofian transpersonal psychology. In a recent presentation at Harvard University, Rick Doblin caricatured my therapy cult analysis while promoting the role of extrasensory perception in MDMA-assisted therapy:

“In some of the critiques, I was called a therapy cult leader on par with Scientology and NXIVM. [...] My response was, ‘Where's all my Rolls-Royces? Where's all my bank accounts?’ […] [The therapy cult analysis is] used on this spiritual, mystical line of attack. Now, there’s a whole other area of experiences…that do seem beyond our more traditional understanding of therapy.... Stan Grof, who's been my mentor and the mentor for a lot of the actual psychedelic researchers, and he helped start transpersonal psychology.... [There’s] what he called this realm of transpersonal experiences.... It can include...information that you pick up beyond the five senses.”

[Side note: I never said that Doblin was the leader, and cultic groups exist on a spectrum.]

Ultimately, it’s clear that these psychedelic therapists invested in pseudoscience believe that what they’re doing is right. Since vulnerable groups are at stake, and predictable patterns of harm will follow from their practices, I have a responsibility to speak up.

Until next time — thanks so much for the support.

Another excellent contribution from the brilliant Devenot, more antidote to the intoxicated hypedelic gold rush. Grof's breathwork is a religious practice and cannot be the basis for an FDA approved pharmaceutical; the cornerstone of psychedelic therapy is the use of persuasion to manipulate belief under the influence of potent psychoactive drugs characterized by suggestibility and lowering defenses to influence and control. Psychedelics have no place as mental health treatments. If people want to use psychedelics for their own self understanding of healing there should be legal access in a decriminalizaiton and harm reduction legal context. The entire effort to turn psychedelics instead into "treatments" for psychiatric diagnosed disorders is a fraud, bolstered by decades of zealotry, pseudoscience, professional self promotion, money-grabbing, and an old boys network of abusers who have been covering for each other's misconduct for decades. How about we reschedule psychedelics according to their actual risk profile and adopt sensible drug policy, instead of empowering a hyped pharmaceutical startup to essentially move in to capture the underground market in a bid to become a new legal drug cartel?

Heh, I'm glad you got some mileage out of that meme.